Howard Pyle chapter header illustration for "The Story of King Arthur" (1903): beautifully framed antique

$110.00

Chapter Header

by Howard Pyle

New York. Charles Scribner's Sons. 1903.

IMAGE INFORMATION

Image Size: H 4.25” x W 6.75”

Matted & Framed: H 10.25” x W 12.75”

Framed Price: $110.00

Packaging and shipping approximately $25.00

HP was a prolific illustrator of stories published in leading national magazines from 1878 until his death in 1911. He is not as well-known as a book illustrator, but during his career, he illustrated more than 150 books. More surprising, the bulk of his pictures were in books he wrote himself!

HP launched this part his career with The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, which Scribner published in 1883. His greatest work was a four-volume set he produced between 1903 and 1910, which contained his illustrated interpretation of the Arthurian legend. No longer writing/drawing for children, the mature author/artist aimed to instruct young adults and adults in the lessons of life. That he appreciated the monumental nature of the project becomes clear in the comment he used to close book four. It reads in part:

And these books are four in number: first, there is the Book of King Arthur; then there is the Book of the Champions of the Round Table; then there is the Book of Sir Launcelot and his companions, and now there is this Book of the Grail and the Passing of Arthur, and this book is the last. For those books comprise a history of all this time ; for though there be many things left untold in them, yet those things are of small consequence.

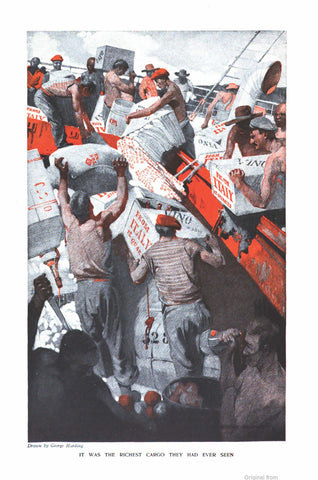

Pyle decorated his books with a variety of antique graphics, including scrolls, ornamental floral patterns, and logo-like geometrical figures. Sometimes he placed header images at the beginning of chapters to add dramatic atmosphere to the part of the story it told. This scene is the header for Chapter 1 of The Story of King Arthur and his Knights.

The artist captured the pageantry and violence of the tournament in which his two armored characters met. His drafting skills are apparent in the detailed ways he portrayed the shock of their collision. The tangle of dark and light spaces and clashing lines hold the eye of the viewer.

Close inspection of the image’s shaded areas show that it was not produced in a halftone photomechanical process. It was probably etched using a “photography -on-the-block” reproduction method, which explains why the image is still clear and bright 115 years later.