Edward Penfield cover illustration for Life (1922): a beautifully framed antique

$295.00

Cover: Life

"All Abroad for 1923"

By Edward Penfield

December 28, 1922 Issue

IMAGE INFORMATION

Image Size: H 11.125” x W 8.625”

Matted & Framed: H 17.00” x W 14.50”

Framed Price: $295.00

Packaging and shipping approximately $22.00

In the fall of 1892, more than a year after EP joined its art staff, Harper and Brothers commissioned poster artist Eugène Grasset to create a poster-style cover for the Christmas issue of its monthly magazine.

EP evidently considered the new art form compatible with his own emerging style. He capitalized on the “poster design” trend by offering to produce another poster cover for the magazine. This image appeared on the cover of Harper’s Monthly Magazine’s April 1893 issue. It had poster characteristics in the sense that its graphics were simple and presented without composition. It featured flat fields of color without blending or shading. And it expressed its message without fanfare or embellishment. What distinguished it from a poster? It attracted the viewer’s gaze, but instead of promoting a product, it insinuated the theme of Harper’s April issue.

One of PE's biographers observed that “Penfield’s first poster to be widely published in the series was well received by the public — and by critics alike.” Herbert Stone, writing in The Chap-Book, explained that “it was unlike anything seen in the land before. It was a poster which forced itself upon one: in design and color it was striking, and yet it was supremely simple throughout. . . . it was theoretically as well as practically good. The artist had attained his ends by the suppression of details: there were no un-necessary lines.” [Ref: DFP, 321; Johnson, 231; Swann-2016, 5. Sited on https://edwardpenfield.com/catalogue/the-complete-harpers-posters/1893/.]

Well-known and highly regarded after ten years at Harper’s, EP found work creating covers and illustrations for Harper’s competitors, including Collier’s, Life, Scribner’s, The Saturday Evening Post, Outing Magazine, and other popular publications.

Since EP’s reputation rested on his poster-designs, it seems odd that after leaving Harper’s he virtually abandoned the style. The reason for this sudden-seeming change may be that after a decade of nouveau art, the public was ready for something different. By the beginning of the new century, magazine-readers may have wanted a fresh look on their magazine covers.

EP had the artistic scope to adjust his style to accommodate the changing tastes of his audience. Instead of plowing farther into artistic design, which was the essence of “the new art” (Art Nouveau), EP moved back toward his classical training. He did this by using his superior drafting skills to build simple, pleasing scenes. His mature works offered little in the way of composition, and his coloring was still done without blending or shading, but he added a quality of illustration by picturing episodes rather than impressions.

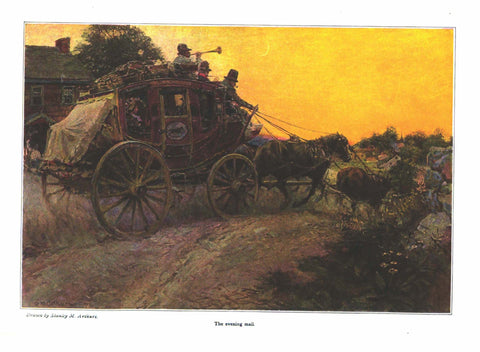

The cover image EP created for Life’s December 28 1922 issue is a complete, well-developed illustration that is easily distinguished from the poster designs that made the artist successful in the 1890s.

EP’s 1922 cover illustration presents a scene that carries the viewer from what has already happened into what is going to happen. The visual experience is entirely different from the ones EP endeavored to create in his poster-style images. In the 1890s, EP used a few brilliant lines and a few pale colored fields to create an impression. Why the change? Who knows. He became older and settled. Perhaps things in his life became meaningful in ways that were different from the way he saw them as a younger man.

EP married Jennie Judd Walker (1868-1950) in 1897. Sometime after that, probably around the time of his departure from Harper’s in 1901, the couple moved to Pelham Manor, New York, which borders on New Rochelle. While living in this pleasant New York suburb, EP became a member of the nation’s largest community of illustrators. Among his cohorts were Franklin Booth, Charles Dana Gibson, Lucian Hitchcock, Frederick Opper, Coles Philips, Frederic Remington, J.C. and F.X. Leyendecker, and later, Norman Rockwell. These men were the nation’ best artist admen and storytellers. Associating with them in the New Rochelle Artists Association, which EP helped to found, surely influenced him as he embarked on his post-Harper’s career.

Line and design were the key characteristics of EP's later style. But, unlike in his earlier work, he used them to produced bright images that told stories. More likely than not, these stories included carriages and horses of which he was so fond. Whether the coach in this image is the one his widow sold to the Boys Scouts in October 1925, I do not know, but it could be. [See Blake Bell’s blog at http://historicpelham.blogspot.com/2014/08/the-revolutionary-era-stage-coach.html.]